The main wing of Melbourne Gaol

The condemned.

Ned Kelly's death mask

23 November 1880

Sir Redmond Barry dies in Melbourne.

1813-1880, Sir Redmond Barry was a British colonial judge, son of Major-General H. G. Barry of Ballyclough, County Cork, Ireland.

Sir Redmond Barry was educated at a military school in Kent and at Trinity College Dublin and was called to the Irish bar in 1838.

He emigrated to Australia and after a short stay at Sydney moved to Melbourne and it is this city he is closely identified.

After practising his profession for some years he became commissioner of the court of requests and after the creation in 1851 of the colony of Victoria out of the Port Philip district of New South Wales became the first solicitor-general with a seat in the legislative and executive councils.

Subsequently he held the offices of judge of the Supreme Court, acting chief-justice and administrator of the government.

He represented Victoria at the London International Exhibition of 1862 and at the Philadelphia Exhibition of 1876.

He was knighted in 1860 and was created K.C.M.G. in 1877. Sir Redmond Barry was the first person in Victoria to take an interest in higher education, and induced the local government to expend large sums of money upon that object.

He was the founder of the University of Melbourne (1853), of which he was the first chancellor, was president of the Melbourne public library (1854), National Gallery and museum and was one of the first to foster the volunteer movement in Australia.

28-29 October 1880

The trial of Ned Kelly at the Supreme Court Melbourne.

Below is a transcript of the exchange between Ned Kelly and Justice Redmond Barry at the final sentencing of Ned Kelly on 30th October 1880.

THE SENTENCING OF EDWARD KELLY

The court crier having called upon all to observe a strict silence while the Judge pronounced the awful sentence of death: his Honour said; "Edward Kelly, the verdict pronounced by the jury is one which you must have fully expected."

The prisoner: Yes, under the circumstances.

His Honour: No circumstances that I can conceive could have altered the result of the trial.

The prisoner: Perhaps not from what you now conceive, but if you had heard me examine the witnesses it would have been different.

His Honour: The facts are so numerous, and so convincing, not only as regards the original offence with which you are charged, but with respect to a long series of transactions covering a period of eighteen months, that no rational person would hesitate to arrive at any other conclusion but that the verdict of the jury is irresistible, and that it is right. I have no desire to inflict on you any personal remarks. It is not becoming that I should endeavour to aggravate the sufferings with which your mind must be sincerely agitated.

The prisoner: No: I don't think that; my mind is as easy as the mind of any man in this world, as I am prepared to show before God and man.

His Honour: It is blasphemous for you to say that. You appear to revel in the idea of having put men to death.

The prisoner: More men than I have put men to death, but I am the last man in the world that would take a man's life. Two years ago - even if my own life was at stake - and I am confident, if I thought a man would shoot me - I would give him a chance of keeping his life, and would part with my own; but if I knew that through him innocent persons' lives were at stake, I certainly would have to shoot him if he forced me to do so; but I would want to know that he was really going to take my innocent life.

His Honour: Your statement involves a cruelly wicked charge of perjury against a phalanx of witnesses.

The prisoner: I dare say; but a day will come, at a bigger Court than this, when we shall see which is right and which is wrong. No matter how long a man lives he is bound to come to judgement somewhere, and as well here as anywhere. It will be different the next time there is a Kelly trial; for they are not all killed. It would have been good for the Crown had I examined the witnesses, and I would have stopped a lot of the reward, I can assure you, and I don't know but I won't do it yet if allowed.

His Honour: An offence of this kind is of no ordinary character. Murders had been discovered which had been committed under circumstances of great atrocity. They proceeded from motives other than those which actuated you. They had their origin in many sources. Some have been committed from a sordid desire to take from others the property they had acquired; some from jealousy, some from a desire of revenge, but yours is a more aggravated crime, and one of larger proportions; for, with a party of men, you took arms against society, organised as it is for mutual protection and for respect of law.

The prisoner: That is how the evidence came out here. It appeared that I deliberately took up arms, of my own accord, and induced the other three to join me, for the purpose of doing nothing but shooting down the police.

His Honour: In new communities, where the bonds of societies are not so well linked together as in older countries, there is unfortunately a class which disregards the evil consequences of crime. Foolish, inconsiderate, ill-conducted, and unprincipled youths unfortunately abound, and unless they are made to consider the consequences of crime, they are led to imitate notorious felons whom they regard as self-made heroes. It is right, therefore, that they should be asked to consider and reflect upon what the life of a felon is. A felon who has cut himself off from all, and who declines all the affections, charities, and all the obligations of society, is as helpless and as degraded as a wild beast of the field; he has nowhere to lay his head; he has no one to prepare for him the comforts of life; he suspects his friends, and he dreads his enemies.

He is in constant alarm lest his pursuers should reach him, and his only hope is that he might lose his life in what he considers a glorious struggle for existence. That is the life of an outlaw or felon, and it would be well for those young men who are so foolish as to consider that it is brave of a man to sacrifice the lives of his fellow creatures in carrying out his own wild ideas, to see that it is a life to be avoided by every possible means, and to reflect that the unfortunate termination of the felon's life is a miserable death. New South Wales joined with Victoria is providing ample inducement to persons to assist in having you and your companions apprehended; but by some spell, which I cannot understand -- a spell which exists in all lawless communities more or less, and which may be attributed either to a sympathy for the outlaws, or a dread of the consequences which would result from the performance of their duty -- no persons were found who would be tempted by the reward or love of country, or the love of order, to give you up.

The love of obedience to the law has been set aside, for reasons difficult to explain, and there is something extremely wrong in a country where a lawless band of men are able to live for eighteen months, disturbing society.

During your short life you have stolen according to your own statements over 200 horses.

The prisoner: Who proves that?

His Honour: More than one witness has testified that you made that statement on several occasions.

The prisoner: That charge has never been proved against me, and it is held in English law that a man is innocent until proven guilty.

His Honour: You are self-accused. The statement was made voluntarily by yourself that you and your companions committed attacks on two banks, and appropriated therefrom large sums of money amounting to several thousands of pounds.

Further, I cannot conceal from myself the fact that an expenditure of 50,000 pounds has been rendered necessary in consequence of acts with which you and your party have been connected. We have had samples of felons, all of whom have come to ignominious deaths. Still the effect expected from their punishment has not been produced. This is much to be deplored. When such examples as those are so often repeated society must be reorganised, or it must soon be seriously affected.

Your unfortunate and miserable companions have died a death which probably you might rather envy, but you are not offered the opportunity.

His Honour then sentenced the prisoner to death in the usual form, ending with the words, May the Lord have mercy on your soul.

The prisoner: I will go a little further than that, and say I will see you there when I go.

7 August 1841

John Kelly placed on board the convict ship andquot;The Prince Regentandquot; in the port of Dublin. On the 7th August and#039;The Prince Regentand#039; sailed from Dublin with 182 convicts on Board.

11 July 1845

John Red Kelly granted his ticket of leave.

11 January 1848

John Red Kelly is granted his Certificate of Freedom.

10 April 1852

Francis Hare arrives in Melbourne Australia from South Africa.

November 1862

19 year old Ernest Flood comes to Melbourne Australia aboard the Shalimar. Ticket number 4269, an Irish immigrant.

February 1869

Harry Powers escapes from Pentridge Prison on the outskirts of Melbourne. He travels north and visits the Kelly home at Eleven Mile Creek in Greta.

8 January 1878

One of the most troublesome and bleakest periods in Victoria's history for public servants, Black Wednesday, 8th January 1878 roughly two hundred senior public servants were dismissed by Sir Graham Berry in retaliation of the Legislative Council's refusal to pass the Appropriation Bill. Berry was Premier of Victoria for only a short period in 1875 although he took office as premier of Victoria again in 1877.

27 June 1880

A special police train departs from Melbourne bound for Beechworth following receipt of news relating to the death of Aaron Sherritt.

29 June 1880

Ned Kelly is transferred from Benalla to the Melbourne Metropolitan Prison and awaits trial.

28-29 October 1880

The trial of Ned Kelly at the Supreme Court Melbourne.

11 November 1880

Ned Kelly is hanged at the Melbourne Metropolitan Prison. He is left hanging from the noose for 30 minutes.

23 November 1880

Sir Redmond Barry dies in Melbourne.

December 1880

The first meeting of the Kelly Reward Board.

8 March 1881

Kelly Reward Board hears its first witness and the hearings continue for a fortnight culminating on 21 March

15 march 1881

The Royal Commission into the Kelly Outbreak has its first meetings and begins hearing evidence several days after the Reward Board's closure.

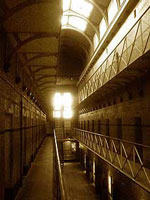

1. Old melbourne Gaol

The Ned Kelly Trail - Melbourne

The Ned Kelly Trail The First andamp; The Final Stop

The first and the final stop on the Ned Kelly Trail is Melbourne. From John'Red' Kelly's arrival here to his eldest son's death by hanging Melbourne has alot to offer the Kelly enthusiast.

The museum has regular exhibitions and visits to Old Melbourne Gaol in Russel Street and Pentridge Prison are a must.

Old Melbourne Gaol

The final stop on the Ned kelly Trail is Old Melbourne Gaol.

The Gaol is bleak, the atmosphere inside, chilling. The museum has plenty on display to keep the visitor enthralled from the heads of the hanged in their individual cells to the gallows where Ned Kelly, only 25 years old was hanged for the murder of the policemen at Stringybark Creek.

Even a petition signed by over 30,000 people demanding clemency was ignored.

thenedkellytrail.com ©2004-2025